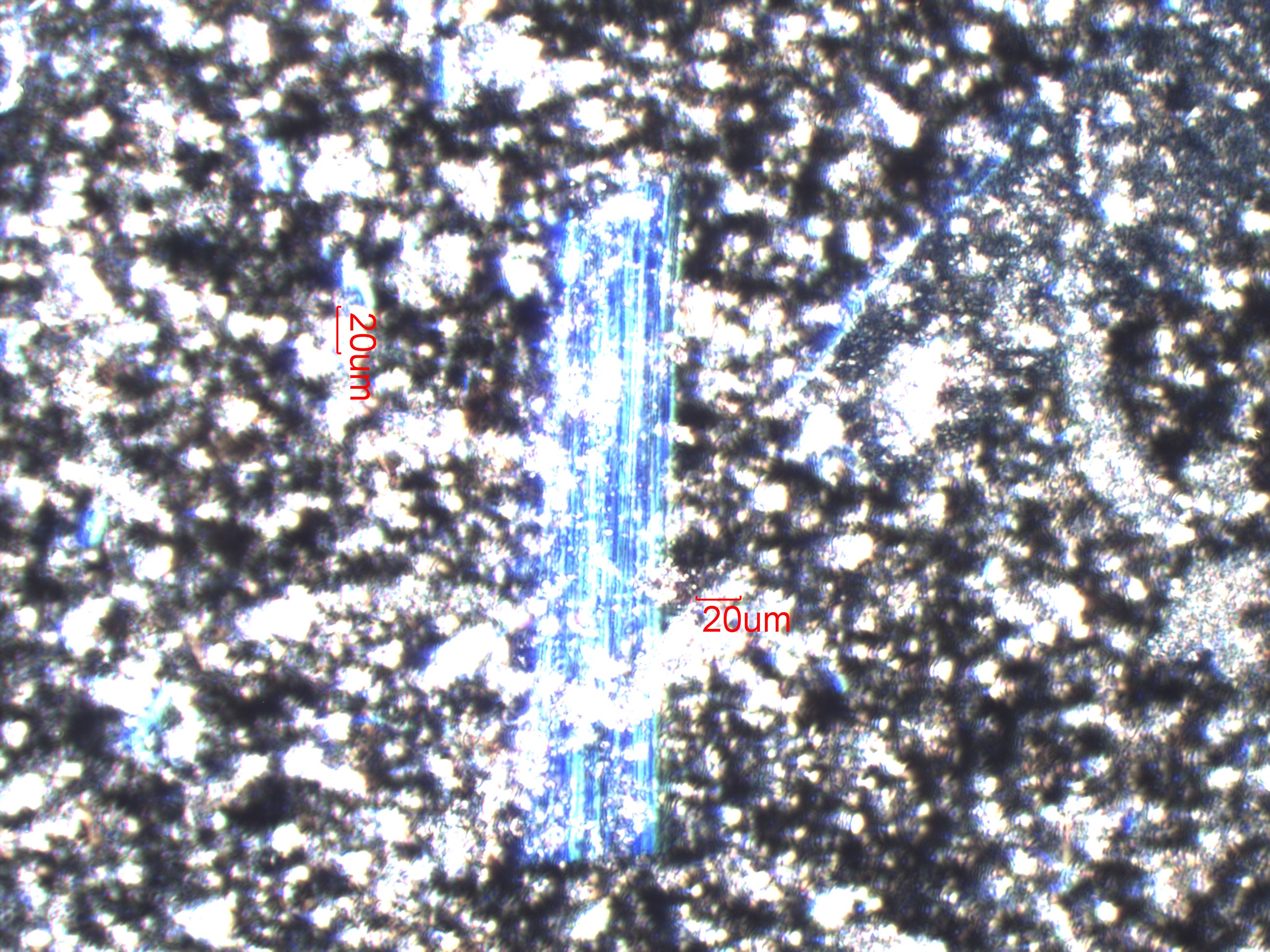

Chrysotile Asbestos

This is a sample of a low refractive index chrysotile. It is in a 1.550 high dispersion liquid. The dispersion color indicates a refractive index perpendicular to the long axis of the fibers That is below this value. The actual refractive index of these fibers across the length is 1.538. This is an example of the persistence of the blue dispersion color.

Definition/Function:

Chrysotile asbestos is the fibrous form of the mineral lizardite of the serpentine group of minerals. Its chemical formula is Mg3[Si2O5](OH)4 with some Fe2+ substituting for Mg. The amount of iron substitution affects the refractive indices and the birefringence. This is the most common form of asbestos used commercially, comprising about 93% of all the asbestos mined. It is also the least hazardous of the asbestos minerals. It is the most flexible of the asbestos minerals and is the one typically used in making asbestos cloth and asbestos paper.Significance in the Environment:

Serpentine is a very common metamorphic mineral. Most mountain ranges contain significant deposits of serpentine. The sands along streams and rivers flowing through these formations often contain chrysotile asbestos sand grains and fibers. Chrysotile asbestos in homes, offices, and schools is generally from asbestos containing construction materials but natural sources can’t be ruled out. Very high exposures have been measured in homes where “free” sand from local mountain stream or river beaches has been used in driveways and sandboxes. See “asbestos sands” in this gallery for an example.Characteristic Features:

Chrysotile has the lowest refractive indices of the six legally defined asbestos minerals. The refractive index along the length of the fiber ranges from 1.545 to 1.558. The refractive index across the fiber ranges from 1.532 to 1.552. Low iron content and missing OH groups drives the refractive index lower. High iron and restructuring following the removal of nearly all of the OH groups increases the refractive index. When thermally modified the refractive indices may go as high as 1.57 and though still a fiber, it looses its x-ray diffraction pattern as chrysotile but has not yet become forsterite. In this form it seems to become even more hazardous than chrysotile. This is the material created on older high temperature thermocouple leads, oven gaskets, and break drums. This form is easily identified using light microscopy but will not show up in an analysis based on x-ray or electron diffraction.

On rare occasions parachrysotile is found with chrysotile. Parachrysotile has a negative sign of elongation, the low refractive index is oriented along the length of the fiber.

Associated Particles:

Commercial materials that contain chrysotile asbestos are often associated with plaster (gypsum, CaSO4-2H2O) and calcite (CaCO3) in textured ceilings and joint compounds, tar in roofing and mastics, paper fiber in sheet material, vinyl and calcite in floor tile, and cement in ceramic board and shingle products. Raw chrysotile is often associated with non- fibrous serpentines and magnetite inclusion.References:

1. Asbestos Textile Institute, HANDBOOK OF ASBESTOS TEXTILES, 3RD EDITION, 1967.2. Campbell, W.J., R.L. Blake, L.L. Brown, E.E. Cather, and J.J. Sjoberg, IC 8751; SELECTED SILICATE MINERALS AND THEIR ASBESTIFORM VARIETIES, US Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Mines Information Circular, 1977

3. Deer, W. A., R. A. Howie, and J. Zussman, AN INTRODCUTION TO THE ROCK-FORMING MINERALS, ISBN 0-582-30094-0, pp. 344-352, 1992

4. Ledoux, R. L. (ed), SHORT COURSE IN MINERALOGICAL TECHNIQUES OF ASBESTOS DETERMINATION, Mineralogical Association of Canada, 1979.

5. Levadie, Benjamin (ed), DEFINITIONS FOR ASBESTOS AND OTHER HEALTH-RELATED SILICATES, ASTM STP 834, 1984.

6. Nolan, R. P., A. M. Langer, M Ross, F.J. Wicks, and R.F. Martin (eds), THE HEALTH EFFECTS OF CHRYSOTILE ASBESTOS, The Canadian Mineralogist, Special Publication 5, 2001.

7. Riordon, P. H. (ed), GEOLOGY OF ASBESTOS DEPOSITS, Society of Mining Engineers, 1981.

8. World Health Organization, ASBESTOS AND OTHER NATURAL MINERAL FIBRES, Environmental Health Criteria 53, 1986.